June 14 | ![]() 0 COMMENTS

0 COMMENTS ![]() print

print

Celtic Minded: faith and football in Parkhead

The unique origins of Scotland’s most successful football club continue to have resonance in a country where anti-Catholic and anti-Irish sentiment remain fixtures in public discourse, concealed under the label of sectarianism. Here, we feature four excerpts from Celtic Minded 4, the fourth volume in a series edited by Dr Joseph Bradley, which looks at the football club, historical bigotry, European pilgrimage, and how Faith and football can provide hope amid abject despair.

Canon Tom White, parish priest of St Mary’s Church in Glasgow, where Celtic FC were formed.

There is the strong and often compelling narrative that faith and football/sport should never mix, and I certainly am aware of those strong arguments. That said, such arguments are not by any stretch of the imagination universal truths.

Indeed, I would say that to hold such a position is almost as absurd as saying that Catholic schools cause division!

Why does the faith foundation of Everton, Southampton or Manchester City and other clubs around the globe cause no issue, just as Catholic schools abroad aren’t problematic?

To hold such a view and not reflect on why it is almost a uniquely Scottish phenomenon, compounded with a failure to challenge some dominant aspects of Scottish culture and national psyche, will serve only a short while.

Maybe until the scapegoat of Catholic schools or indeed a culturally Irish and Catholic football club dies and society goes on to pursue yet another scapegoat.

At this point I must admit that during my first five years at St Mary’s I was indifferent to the ‘Celtic’ dynamic of our parish’s history. Relations with the club were not dead, just indifferent.

There was always the understanding that perhaps if there was an hour of need the club may help.

We had the odd parish fundraiser at the Kerrydale Suite, but I am not sure we received ‘family and friends rates’ either!

It was at these fundraisers that the parish’s most famous and arguably most treasured son, Tommy Burns, would want to support us with his presence and his legendary singing of Mack the Knife!

Everyone with a depth of following of Celtic will know of Tommy’s heroic but ultimately failed battle against cancer. It was through this tragic loss for his family and club that something was awoken in me.

I had often seen Tommy at weekday Mass in St Mary’s but I, like many of the parishioners and much to their credit, would say no more than ‘hello Tommy,’ and leave him in peace to get on with his prayers.

Now Tommy was dead, and was making one last journey to his spiritual home of St Mary’s. The vast crowd which gathered outside for the Requiem Mass eventually closed Abercromby Street as the Celtic Family gathered to mourn and pray for one of their own.

With St Mary’s packed to capacity (around 1,600), treble the number outside, and yet more at the stadium, it became obvious that Glasgow was burying one of its giants.

Not since the funeral of the late Cardinal Thomas Winning had the Catholic Church witnessed the faithful gather in such numbers for a funeral.

Just like the crowd outside St Andrew’s Cathedral on the morning of Cardinal Winning’s funeral, those who gathered outside St Mary’s gathered with sincerity of heart and clarity of purpose: they were here to pray for the repose of Tommy’s soul and the comforting of his dear wife Rosemary and their family.

From that day on I was aware more than ever that the Catholic identity of Celtic was not simply a thing of the past, but was something alive and active.

No other football club in Britain could, along with huge numbers of its support, come together and actively and genuinely be part of, participate in, and share in the celebration of Mass for one of their own: this was a clear demonstration of Celtic’s uniqueness—at the very least, in Scottish and British football society.

Dr Roisín Coll and Bob Davis, St Andrew’s Foundation for Catholic Teacher Training.

From its origins, Celtic Football Club has had a close connection with Europe.

The Marist brothers, an order founded in France in 1816 by Fr Jean-Claude Colin, afforded the club from its foundation a sense of belonging to the wider international networks of the Catholic Church and especially to its charitable presence in the great and growing European cities.

The club’s founder, Br Walfrid, intended that Celtic from its outset would address the plight of Glasgow’s Irish Catholic poor whilst maintaining the population within the orbit of the wider Church and its spiritual life.

From this rich genealogy there arose among the club’s supporters a natural sense of attachment to wider European traditions and institutions that predated the emergence of a European platform for football competition itself.

Important work by Raymond McCluskey (2006) has overturned earlier simplistic stereotypes of a working-class Irish Catholic community of narrowed cultural horizons by highlighting the presence across the community of broader European expressions of Catholic identity—such as parish support of and participation in pilgrimages to Lourdes, Rome and Fatima; the establishment of and involvement in prayer groups and other organisations centred on the patronage and charisma of a range of European saints and spiritual leaders (eg St Vincent De Paul); and the continuing presence at the heart of the community of orders and congregations with deep continental roots (eg, Jesuits, Redemptorists, Sisters of Mercy).

All of these features were, of course, set in the context of a Church with a common language of liturgy and ideas spanning those same European nations that would soon prove to be the crucible of 20th century European football played at the highest levels of international excellence.

Hence the daily fabric of working class Irish Catholic life in Scotland was routinely, even unconsciously, imprinted with ‘the idea of Europe.’

Despite the advance of secularism, it seems clear that the cultural roots of these inclinations are fundamentally religious in origin.

They stem from the undoubted imprint of the Catholic Faith and its forms of life on the community and its cultural practices over many generations.

Central to this is a shared life-affirming language of Faith, devotion, reverence, solidarity, effort and goodwill, sustaining fans on their travels to locations familiar and unfamiliar on the pilgrim routes of Europe.

Jim Craig, former Celtic FC player and Lisbon Lion.

When I was a laddie, it did not take long for me to come across what is politely called, regardless of how accurate or inaccurate a description, Glasgow’s ‘Religious Divide.’

In my last two years at school, I was chosen for the Scottish Schools Under-18 side, whose only fixture each year at that time was against England.

There were trials every year for this team, as there had been for the Glasgow Schools XI, which I also played for between 1958 and 1961.

It was at one of these trial matches that a certain incident reminded me that religious discrimination could be not only disconcerting and upsetting, it could also be career-changing—or perhaps ‘career-hindering’ might be a better expression. My experience was in football.

God help, literally, others in various other employments who were held back because of ethnic and/or religious discrimination against them.

The Rangers scout who attended all these trial matches was a former star of the club from the 1930s and 1940s. I spoke to him regularly and found him a most pleasant and unassuming man.

After one game, in which I thought I had played very well, I went across to see him. “How did I do tonight, then?” I asked. He smiled and replied, “You were very good, Jim.”

I then came in with my well-rehearsed punch-line. “Well, have you got the papers with you. I’m ready to sign any time.” He laughed and held up his hands. “Ah! Jim… you know how it is, son.”

When I arrived at Celtic Park in the autumn of 1965, I was not expecting anything even resembling the religious discrimination that was well known in and around Glasgow’s other big side and indeed beyond in wider society.

As expected, I found none. Indeed, as had always been the case, the players and management came from differing ethnic and religious backgrounds.

Training and playing with my teammates was not only good fun but also a great life experience.

While we certainly were not in each other’s houses all the time, we all got on well.

We were Catholics and Protestants, of Irish and Scots descent, and big Billy was, of course, also part Lithuanian.

There was no prejudice, discrimination or bias that encroached in our relationships: we were part of the Celtic Family and all were or became ‘Celtic Minded,’ through and through.

Emma O’Neil, Nine Muses Br Walfrid awareness campaign.

There are numerous understandings of what constitutes Faith and they never ring truer than when it comes to Celtic Football Club.

It is really hard to pinpoint where my personal religious experiences with Celtic began but I can think all day long of encounters I have had with my Faith and Celtic.

I feel so thankful for my blessings, friends and family, and many other things that have restored my Faith over the years.

I suppose my own experience with Faith and religion really came to fruition when in my teenage years I was diagnosed with acute anorexia nervosa. Aged 15, I had a rapid decline in the depths of an eating disorder that would take away my whole adolescence.

My parents were distraught throughout this period of pain shared by our family and it is during this time that I remember my mum being really called back to her Faith.

She invited religious messengers into the house to pray for me, share presentations, watch religious short stories and read from the Bible. She took me back to church and prayed for me openly.

When I was later hospitalised for the eating disorder, I think I felt I was truly praying for myself: how was I going to get through this?

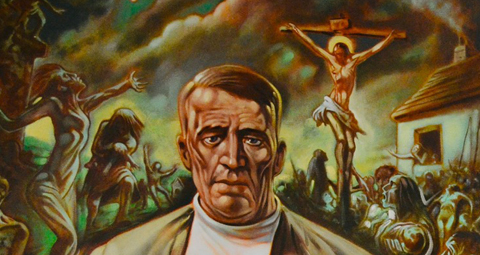

I have in my possession a Peter Howson pastel, the first in my collection, called The Third Step.

It depicts a naked man lying in the dirt, dragging himself to the Saviour, with a church in the distance. While ill, this piece of art illustrated everything was and what I was trying to do, and it hung, despite its worth, on my hospital room wall to inspire me.

I had struck up a friendship with Peter Howson a few years after that and he used to come to visit me in hospital.

Unfortunately, every relapse in my anorexia I had was worse than the previous time. Ultimately reaching under three stones I was a shell of my former self: controlled by anorexia.

Peter would send me Christmas cards with religious figures and scriptures from the Bible, each giving me more Faith to keep going.

Later I’d go on to commission works by him that were drawn and painted from paragraphs I’d written about my illness and my idea of religion.

Dark, dark paragraphs that only looking back can I now see how ill I was, though in denial at the time.

I’ve always had a connection with Celtic but this grew massively when I started exploring and researching the club and its community’s religious and Faith origins.

It might be worth noting at this stage that I am completely healthy and have been for around eight years. I now have two children and work hard at my business.

I have fought the monster that is my eating disorder whilst exploring the faith around Celtic FC. Much of this has come about from learning about, and learning from, Br Walfrid’s life, and, most importantly, his character of strength, kindness, gumption, and tenacity.

Throughout this time of exploring Br Walfrid in the context of the Great Irish Hunger and in the famous depiction of Walfrid by Peter Howson (left), I have been healthy and thankful. This is not a coincidence.

All the qualities of Br Walfrid which I have come to learn about, have arisen essentially from this painting. Howson’s painting of Walfrid inspires me immensely.

I have never felt closer to my Faith than when I have been drawn towards the Celtic Minded community by Br Walfrid.

— Celtic Minded 4 is priced £11.99 and is available from Argyll Publishing. Tel 01369 820345 for details or visit

www.thirstybooks.com