BY Daniel Harkins | November 23 | ![]() 0 COMMENTS

0 COMMENTS ![]() print

print

1918: a monumental year for Catholic education

The SCO archives reveal the concerns of Catholic community at the time of the Education Act

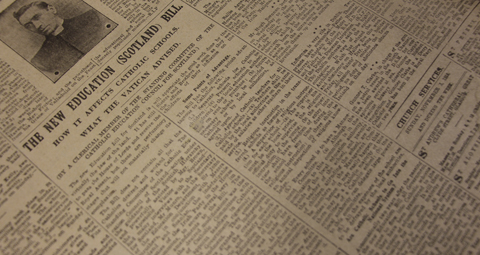

The 1918 editions of the Scottish Catholic Observer —or as it was then, the Glasgow Observer and Catholic Herald—give an insight into the Catholic community at the time of the 1918 Education (Scotland) Act.

In those days, the front page of the Observer, as with many papers, was taken up entirely by advertisements. Alongside mundane postings on ‘summer fashions’ and ‘Irish produce’ are wild claims by the Botanic Medical of Glasgow that their special herbs can ‘CURE ALL DISEASES.’

Inside, news of the last days of the First World War dominate, with weekly photos of the Catholic men killed in action, and efforts to recruit 12,000 women into war service as late as September of 1918: “Your boy and your girl pal are in it,” one ad reads, “Why aren’t you? “

Beneath that ad, an article makes an argument that could well be seen in the pages of today’s SCO. As the Education Act implementation approached, the writer bemoaned the lack of ‘dogmatic teaching’ of Religious Education.

“From all quarters the wail of the presbyteries of churches over the insecurity of religious teaching under the new Education Bill issues forth. Why the great outcry… over a subject that has lain dormant so long?”

Religion, the article said, has become a ‘vague, creedless emotion indulged in according to each man’s whim of what he is pleased to call his conscience.’

Readers in presbyteries may recall their own wails of a similar nature in recent years, but we can take comfort from the fact that our fears now, were the same fears then, and yet our Faith and our schools still stand.

The article also argued that ‘today, there is a great struggle going on between those who would organise society without religion and those who claim a place for religion in society,’ and that ‘churches are now regarded by thousands as the hereditary enemy of the ideals of the working classes.’

A century later

100 years on, the Church still has a voice in Scottish society, and the goal of those early 20th century secularists to eradicate religion in public life has not been realised.

One obsession of the early 20th century Observer was Celtic FC. Each edition carried an extensive report on the Glasgow football club from ‘Man in the Know.’

This is not surprising, given the Glasgow Observer was founded by some of the men who would go on to found Celtic a few years later, and many of the country’s Catholics were Irish or had Irish parents. Indeed, every edition of the paper that year carried extensive reports on Ireland, and the calls for Home Rule.

A report in the September 28, 1918 edition of the SCO finds some opposition from the Kirk to details in the education bill. It explains concerns from the Kirk about Catholic priests being allowed to oversee religious education in a supervisor role.

The dispute was picked up in the October 5 edition, with the paper reporting that the Presbyterian ‘zealots’ wanted to stop priests from being able to enter the state-funded Catholic schools at any time.

Should the supervisor proposal be removed, and the ability of priests to enter the school be restricted, it ‘would mean simply that the Catholics could not touch with a fifty-foot pole the new Education Act,’ the paper said.

1918 election

The pages leading up to the signing of the Education Act on November 21 are also filled with stories on the upcoming general election. The 1918 election was the first in which women over 30 and men over 21 could vote. It would have lasting consequences for Ireland, as Sinn Fein members swept the board, leading to the Irish War of Independence.

The SCO made no pretence of being politically neutral in the vote. In its advocacy for Ireland and Catholics, it urged voters not to abstain from UK parliamentary politics, as was Sinn Féin’s policy, and called on readers to ‘join the Labour Party’ as it will be ‘more progressive, more humane’ than the coalition government that was in power at the time, arguing that the party was the best opportunity to provide Ireland its freedom.

“You will be told by all sorts of people that you are on a dangerous path, that you are associating with extreme men,” it said, adding: “If you are to vote Tory, will you not be in the company of the Orange and Hun extreme men?”

The Observer’s political position may well have been influenced by the fact that its managing editor, David John Mitchell Quin, was standing as a Labour candidate in Central Glasgow.

Neither Mr Quin nor Labour would win the election, which returned a victory for both the coalition and Sinn Féin.

Concerns

A month from the signing of the Education Act, concerns were raised about the fate of the only Catholic school for deaf children in Scotland. There were six institutions for ‘deaf and dumb, semi-deaf or semi-mute’ children in Scotland in 1918, five of which were non-Catholic. The Observer report said the disabled Catholic pupils faced being raised ‘devoid of any knowledge of God, religion or soul,’ as a result of being educated in schools where the only option was to opt out of ‘Protestant’ religious instruction. The report called for Catholic representation on a committee to explore the issues facing ‘semi-deaf and semi-mute schools and institutions in Scotland.’

In the October 19 edition, a letter writer, W Devlin of Irvine, asked why the Education Bill was ‘apparently only a subject for secret diplomacy.’

“I have been told that our Holy Father Benedict XV has informed our bishops that it is lawful for the Catholic schools to come under the national system, provided that Catholic interests are made secure. But are they made secure? No one seems to know,” he writes. “If this bill results in the destruction of all those vital things for which our people have suffered in the past, the cause of that calamity will be our weakness.”

The same edition reported that the above mentioned dispute over priests as supervisors in schools had been resolved. The paper now maintained that Catholics did not seek to ‘wreck the bill’ but that unless necessary safeguards were met, Catholic schools would stay out of the state system.

The Great War ends

The following week, the newspaper welcomed the end of the war, as Germany had ‘admitted defeat’ and accepted armistice conditions from the US President.

On November 2, the SCO reported that the Education Bill was ‘virtually the law of the land.’

“It has still to pass the House of Lords and receive the Royal Assent, but these are perfunctory stages that will not materially change its complexion,” wrote a clerical member for the standing committee of the Catholic Education Council for Scotland.

The committee worked under the Scottish hierarchy, and, according to the article, while the bill ‘does not contain all that Catholics desired or worked for,’ a number of amendments had been achieved.

These included a clause, written by the Catholic committee, which ensured new Catholic schools could be built after the act was passed. The committee also achieved concessions on supervisors of religious instruction. Without the amendment, priests would have been ‘entirely excluded from the school,’ the report says.

One priority for the committee was the inclusion of ‘Catholic committees with powers to appoint teachers in Catholic schools.’ However, this was ‘rigorously refused’ by the government. Instead, the act allowed for ‘approved Catholic teachers for all Catholic schools.’

Proposals

The article also revealed that the Holy See, during the bill’s reading in parliament, instructed that the proposals had to be accepted by Catholics before it could pass.

The article concluded that the sooner Catholic schools transferred to local education authorities, the ‘sooner shall we be relieved of our school financial burdens and justice done to Catholic teachers in providing them with salaries which will be more commensurate with their self-denying devotion to duty in so largely fostering and preserving the Faith of the children committed to their unwearied care.’

One interesting provision in the act is for ‘an annual inspection of religious knowledge,’ though this is not currently used by the Church.

With the act all but passed, concerns moved to parents’ role in Catholic education. An article on November 16 argued that too many parents regard ‘training of the child as a prerogative of the state, rather than a primal parental duty.’

“It is impossible to understand how anyone laying claim to the name of Catholic can lightly send a Catholic child to a non-Catholic school,” the article says.

Bishop of Aberdeen

That point would be echoed by the Bishop of Aberdeen, who wrote on December 7 of the ‘splendid work’ being done by ‘often ill-paid’ teachers, but warned that the ‘first duty of a Catholic parent is to obtain a thoroughly Catholic education for his children.’

By the end of the year, concern had moved on to teachers’ salaries, with the Catholic Teachers Association and the Catholic Teachers’ Union lobbying the Secretary for Scotland for an ‘urgent’ release of funds to increase salaries.

Glasgow Archdiocese meanwhile, appointed a committee of school managers to scrutinise the act, and ensure the transfer of the archdiocese school estate to the local authority as soon as possible.

The pages of the 1918 Observer catalogue a tough year for the country. But it would end with two highs: the end of the war, and one of the most monumental victories for Catholicism in Scotland.

That sense of victory, and of hope for the future, was illustrated in an article on the armistice by Canon McNairney, the parish of priest of St Peter’s in Partick, Glasgow.

He wrote: “The long night of war is over, and the day of peace is dawning. May it indeed be a lasting peace.

“If all things are to be renewed in Christ, and the world is to be a better place than it was before the war, we must each do our share in the work. It is not great things I speak of. Our lives are for the most part made up of little things, but they are little things of mighty import. We are Catholics. We are proud of the name.”

Little did he know that the act passed that very same week would play such a vital role in achieving those goals, lifting thousands out of poverty, and proving that Catholic schools are good for Scotland.